UD: March 2019

Alcohol, especially beer, played a particularly important role in Celtic society. While imported wine was favoured among the richer classes, the common drink of the Celts was a form of beer called kormi /korma (*PC Kormi, OIr cuirm, OW curum, Gaul. Curmi; Matasovic EDPC:217; Diosc. De mat. Med. 2):

“And the liquor which is, among the rich, wine brought from Italy or from the country around Massalia; and this is drunk unmixed, but sometimes a little water is mixed with it. But among the poorer classes what is drunk is a beer made of wheat prepared with honey, and oftener still without any honey; and they call it Κορμα” (Ath. IV:36).

Classical authors and archaeological finds paint a fascinating picture of Celtic banquets. Even allowing for the exaggeration common to classical depictions of the ‘barbarians’, enormous vessels like the Vix Krater or Gundestrup Cauldron, attest to the immense scale and lavishness of some of these occasions.

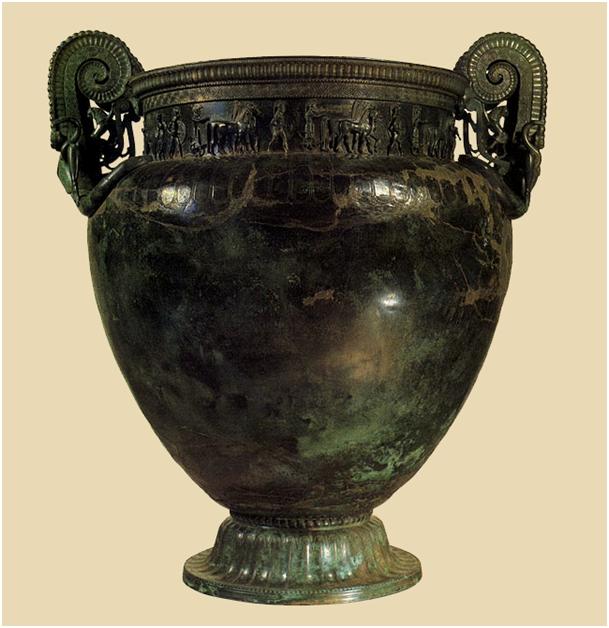

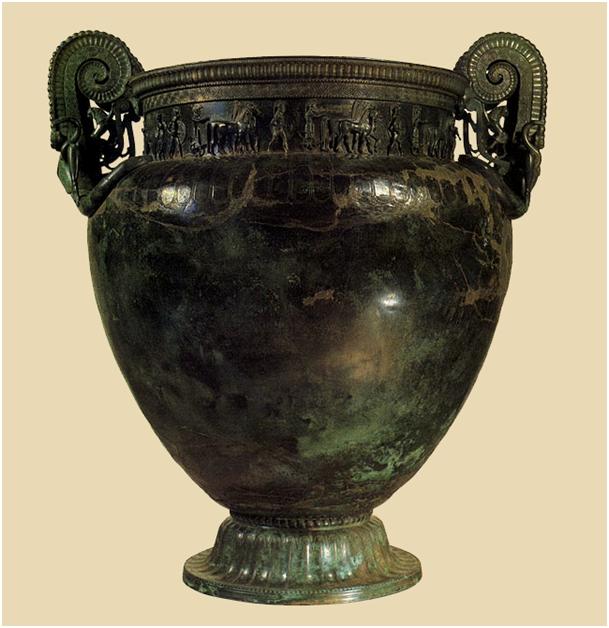

THE VIX KRATER

(late 6th c. BC)

At Vix, where the Celts settled in the 6th century BC, a fortress was erected, and in a circle of around 10 km. are dotted dozens of burial sites. On the southern side of these mounds the most spectacular tomb, that of the Lady of Vix, was discovered in 1953. The Celtic Princess was buried with a number of remarkable artifacts including a magnificent bronze krater of Etruscan or Greek origin, 1.63 m. in height, weighing 208 kg., and made to contain 1,100 liters (290 gallons) of liquid; it is the largest known metal vessel from antiquity.

The Gundestrup Cauldron

Made by Thracian craftsmen for the Celtic Scordisci, the Gundestrup cauldron is the most spectacular of Celto-Thracian artifacts, and the finest example of late Iron Age European silverwork.

On the Gundestrup Cauldron see also: https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2016/09/06/the-gundestrup-ghosts-hidden-images-in-the-gundestrup-cauldron/

In terms of archaeological data, particularly interesting is recently published archaeobotanical evidence for beer-making in southeastern France, which confirms classical accounts of the importance of beer among the Celts. An archaeological sample from a fifth century BC Celtic house at the site of Roquepertuse produced a concentration of carbonized barley (Hordeum vulgare) grains. The sample was taken from the floor of the dwelling, close to a hearth and an oven.

The barley grains are predominantly sprouted and the assemblage represents the remains of deliberate malting, related to beer-brewing. An oven was discovered nearby which was used to stop the germination process at the desired level by drying or roasting the grain (Bouby et al 2011).

The carbonized barley grains from the Celtic site at Roquepertuse

Celtic beer tankard (bronze/wood) from Langstone (Newport), Wales (1st c. AD)

The Langstone tankard is a Celtic from of drinking vessel used for communal drinking of beer and cider and especially prevalent across western Britain

Celtic tankard of wood (yew) and bronze discovered in a bog at Trawsfynydd (Gwynedd), Wales (ca. 50 BC). The cast bronze handle of the vessel is decorated with triskele motifs, indicating that it had a ceremonial/religious function.

On the significance of the triskele in Celtic culture:

https://www.academia.edu/11899946/An_Tr%C3%ADbh%C3%ADs_Mh%C3%B2r_-_On_The_Triskelion_in_Iron_Age_Celtic_Culture

Bronze bowls and wine strainer with triskele motif in the perforation pattern, from Langstone (Newport), Wales (ca. 50 AD)

THE MEN WHO COULDN’T DIE

The Celtic custom of drinking neat wine and large quantities of beer was alien to the classical Greek and Roman cultures. Poseidonius (cited in Ath. 4:36) describes their ‘shocking’ dining habits:

“and they drink it (beer) out of the same cup, in small draughts, not drinking more than a cythus at a time, but they take frequent draughts”. When enough refreshment had been partaken of, mealtimes often became quite energetic occasions – “The Celts sometimes engage in single combat at dinner. Assembling in arms they engage in a mock battle drill”. Although mostly good natured, these ‘games’ could often escalate and become deadly:

“Sometimes wounds are inflicted, and irritation caused by this may lead even to the slaying of the opponent unless by-standers hold them back” (Ath. op cit).

Diodoros (1st c. BC) attempts to explain this ‘insane’ custom by reference to Celtic belief in metempsychosis:

“And it is their custom, even during the course of the meal, to seize upon any trivial matter as an occasion for keen disputation and then to challenge one another to single combat, without any regard for their lives; for the belief of Pythagoras prevails among them, that the souls of men are immortal and that after a prescribed number of years they commence upon a new life, the soul entering into another body”.

(Diodorus V.28:5-6)

On the Celtic belief in Metempsychosis see:

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2013/12/10/catubodua-queen-of-death/

The Aylesford ‘Bucket’

This sort of receptacle, with a capacity of 3-5 liters (6-9 pints), formed part of a drinking service for wine, which was imported in quantity and drunk during feasts, probably linked to religious ceremonies.

(1st c. BC)

https://www.academia.edu/23291021/CELTIC_CEREMONIAL_BUCKETS_AND_BELGIC_EXPANSION

THE GREAT BEER GOD

The Celts also ‘exported’ their beer to Thrace during the eastern expansion of the 4th/ 3rd c. BC, and the fact that the liquid nectar was ‘worshipped’ among the Balkan Celts is testified to in the name of the local God (epithet of Apollo) – Κυρμιληνός – in an inscription from Ezerovo, Bulgaria (KDP 236; Detschew 1957:271), the Celtic epithet of the Greek God being yet another example of the synthesis of cultures in Thrace during this period (Detschew op cit.). Besides Κυρμιληνός, the element also occurs in many Celtic personal names such as Curmillus, Curmissus etc. (Holder AC 1: 1203), indicating that these individuals were probably brewers by profession.

The last word on this subject undoubtedly belongs to a Pannonian Celt called Curmi-Sagius (Meid 2005), whose name literally means ‘The Beer Seeker’ / ‘He Who Searched For Beer’ – apparently a particularly devoted disciple of the Great Beer God…

Sláinte!

(Modern) Literature Cited

Bergquist A.K., Taylor, T. F. (1987). The origin of the Gundestrup cauldron. In: Antiquity 61: 10-24.

Bouby L. Boissinot P., Marinval P. (2011). Never Mind the Bottle. Archaeobotanical Evidence of Beer-brewing in Mediterranean France and the Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages During the 5th Century BC. In: Human Ecology, June 2011, Volume 39, Issue 3, pp 351-360

Detschew D. (1957) Die thrakischen Sprachreste. Wien

Haywood J. (2004). The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age.

Holder A. Alt-celtischer Sprachschatz. B. 1–3. Leipzig 1896-1910

Kruta V. (2004)The Celts – History and Civilization.

Meid W. (2005). Keltische Personennamen in Pannonien, Archaeolingua, Budapest.

Taylor T. (1992). The Gundestrup cauldron. In: Scientific American, 266: 84-89.

Mac Congail