UD: April 2019

The Celtic goddess Epona is specifically identified by her horse symbolism. Her name is etymologically related to a Celtic word for horse, and is defined iconographically by the presence of one or more horses, being generally depicted either riding side-saddle on a mare or between two ponies or horses. Epigraphic dedications and images of Epona indicate her immense popularity within the Celtic world, and she was venerated particularly in the east of Gaul and the Rhineland, but known also across the continent from Britain to the Balkans (Green 1992. P. 204 – 207).

Relief plate devoted to the Celtic goddess Epona, found 1583 in the ruins of a Roman villa rustica at Freiberg am Neckar (Baden-Württemberg), Germany

ETYMOLOGY

The name of the goddess derives from the Proto-Celtic *ekWo- ‘horse’, Gaulish Epos – ‘Horse’ (Olr. ech, Ogam EQO-DDI, W: MW ebawl ‘foal’ [m] (GPC ebol) BRET: OBret. eb ‘horse’, ebol ‘foal’, MBret. ebeul [m] CO: OCo. ebol gl. Pullus CELTIB: Ekua-laku [PN] (A.63). Gaulish Equos – ‘name of the ninth month’ (Coligny) may be an archaic form (with preserved qu < *kw). The Brit. forms (except OBret. eb) are from a derivative *ekwalo- (cf. also Celtib. ekualaku and ekualakos, which has been interpreted as a Nom. sg. of an adjective ‘belonging to ekuala’; Matasovic (2009).

The element is common in Celtic names such as Epacus, Epasius, Eppius, Eppia, Επηνοσ (Epenos), Epomeduos, Eporedorix, and the names of tribes such as the Επίδιοι (Epidii) in Scotland, or in placenames such as Epomanduodurum in France (Delmarre pp. 163-164 and pp. 355-389), while Indo- European cognates of Gaulish epo- are frequent in PN’s over a wide area.

Gaulish coin of the Meldi tribe (60-50 BC), bearing the abbreviated legend ΕΠΗΝΟ

Marble relief from Saint-Béat (Haute-Garonne) France, depicting Epona, the Celtic horse Goddess (enthroned), surrounded by geometric symbols and fantastic aquatic/hybrid creatures.

(1/2 c. AD)

It should be noted, however, that the supposed autonomy of Celtic civilization in Gaul suffered a major setback with Fernand Benoit’s study of the funereal symbolism of the horseman with the serpent-tailed (“anguiforme”) daemon, which he established as a theme of victory over death, and Epona; both he found to be late manifestations of Mediterranean-influenced symbolism, which had reached Gaul through contacts with the east (Benoît 1950).

Unusually for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities, the worship of Epona, one of the few Celtic divinities worshiped in Rome itself, was widespread in the Roman Empire between the first and third centuries AD (see below).

Epona’s name is known through dedicatory inscriptions (mostly in Latin or Greek), and through passing references in Latin literature. Although the name Epona is Celtic, no inscriptions to the goddess have been found in the Celtic languages, as the custom of setting up dedications was introduced by the Romans. The most northerly Epona inscription comes from Auchendavy (Strathkelvin District, Strathclyde Region) in Scotland. The altar was unearthed in 1771 during excavations of the Forth and Clyde canal and is now in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow.

The altar from Auchendavy (Strathkelvin District, Strathclyde Region, Scotland)

Marti /

Minervae /

Campestri/bus Herc(u)l(i) /

Eponae /

Victoriae /

M(arcus) Coccei(us) /

Firmus /

|(centurio) leg(ionis) II Aug(ustae)

The altar is dedicated to Mars, Minerva, the Goddesses of the Parade Ground, Hercules, Epona, and Victory by Marcus Cocceius Firmus, a centurion of the 2nd Legion, and most likely a member of the emperor Marcus Aurelius’ bodyguard.

Epona Enthroned on a sandstone relief from the temple area of the ancient settlement of Brigantium / Bregenz (Vorarlberg), Austria

(1-2 c. AD)

Silver plate depicting Epona enthroned, from the Petrijanec Hoard in northern Croatia (Dated to 294 AD)

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2017/01/10/epona-enthroned-the-celtic-horse-goddess-on-a-roman-silver-plate-from-petrijanec-croatia/

EPONA IN THRACE

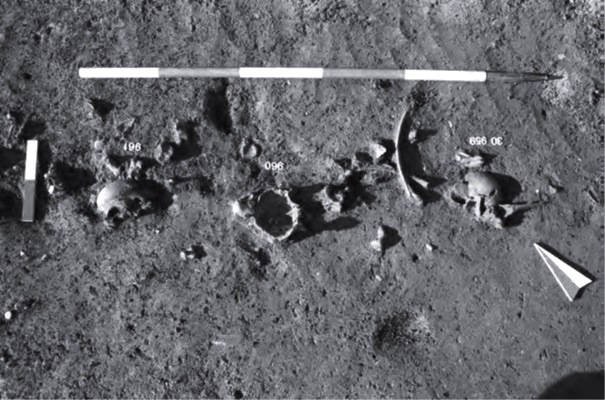

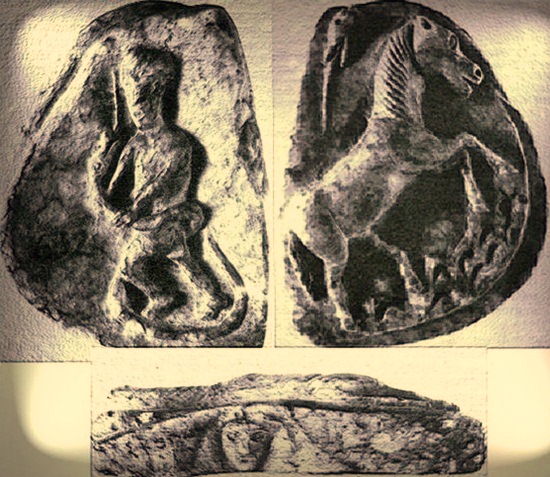

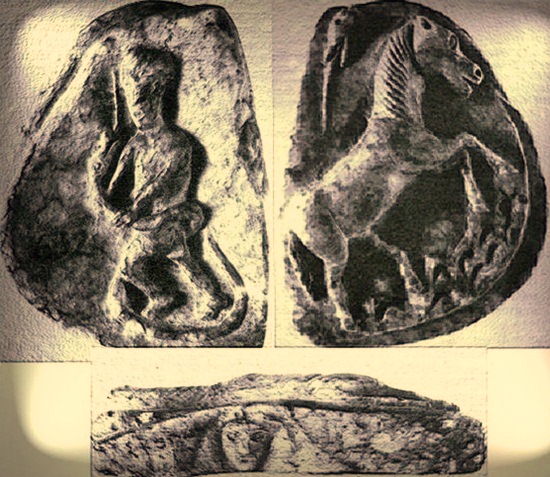

The earliest evidence for the worship of Epona in Thrace comes from a small inscribed cult relief, discovered in the Sofia area of western Bulgaria. Dated to the late 4th/ 3rd c. BC, the carved ‘Scordus’ stone illustrates well the religious beliefs of the Celtic Scordisci who obviously worshiped Epona, the tribal ancestor-god and the warrior hero. The ritual function of the object is unclear, but carved stones displaying various imagery were widely used in Celtic cult practices. On one side of the relief a mare is depicted, which has been interpreted as a hippomorphic personification of Epona (Green 1986: 91-94, 173-174; 1992: 90-92; 1995: 479; Manov 1993 with cited lit.).

As mentioned, Epona was known as a deity of fertility and prosperity but she was also associated with beliefs relevant to death and the underworld. The other side of the carved stone shows a man in a fight to the death with an enormous snake. On the edge of the Sofia relief, a second snake is depicted together with a male facing to the front contiguous to a short incised inscription – ΣΚΟΡΔΟ (= genitive: ‘belonging to Scordus), i.e. the tribal eponym and ancestor-god Scordus, attested as Scordiscus in the sources (Appianus, Illyr. 2) (Manov 1993).

Inscribed cult relief bearing a dedication to the Celtic tribal God Scordus (Sofia region, w. Bulgaria. 4th – 3rd c. BC)

(After Manov 1993)

See:

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2012/05/12/the-scordisci-wars/

The survival and popularity of the cult of the Celtic horse goddess in Thrace in the Roman period is testified to by a number of inscriptions and depictions of Epona during this period:

An example from Aptaat (Kruschari district, Dobrich region, northeastern Bulgaria) is one of the few inscriptions in Greek (Reinach 1902 p.237; Magnen & Thévenot #33 (inscription), #219 (depiction). It does not name Epona explicitly, but is carved on an imperial type stone bas-relief of Epona seated between two horses which face inwards, offering them food from her lap. Passers by were thus expected to recognize the goddess by her attributes alone, the name being considered superfluous.

Θεαν έπηχοον Αίλιος Πανλίν [ος άνεθη]

‘Aelius Paulinus has given this image of the auspicious goddess’.

The inscription is dated to the beginning to the 2nd century A.D. (100 – 122) when the Celtic Cohors II Gallorum equitata was stationed in Moesia.

Lead cult plaque from Thrace (2/3 century) depicting Epona and the ‘Danubian Horsemen’ – a magnificent example of the synthesis of Thracian and Celtic religious beliefs during the Roman period.

for discussion see: http://atlanticreligion.com/2014/08/23/epona-and-the-cult-of-the-danubian-horsemen/; also https://www.academia.edu/4004264/Contribution_to_the_Study_of_the_Danubian_Horsemen_Cult_Iconographic_Syncretism_of_the_Danubian_Goddess_and_Celtic_Fertility_Deities

An altar with an inscription to the Celtic Goddess Epona (Deae Eponae Reginae) by Valerius Rufus, beneficiaries consularis legionis of the XI legion confirms Celtic presence in the Roman forces at the Abritus military complex, also in northeastern Bulgaria. The inscription has been dated to 215 AD (Иванов, Р. 1993:29). Other evidence for the worship of the Celtic horse Goddess in Thrace comes from Augustae (modern Hurletz, Koslodui district, Vratza region) in northwestern Bulgaria where a marble votive tablet to the Celtic Goddess has been discovered (Reinach S. Rép. Des reliefs II, 153, nr. 3; Seure, Arch. Thrace II, 177; Kazarow 1938: P. 85. Inv no. 399. Fig. 224), and a bas-relief of the goddess from Plovdiv (Magnen, Thévenot 1953; Tudor 1997).

Marble relief of the Celtic goddess with the Thracian horseman – from Augustae (mod. Hurletz) near Koslodui on the Danube in NW Bulgaria. (1st – 2nd c. AD)

Marble relief of the Celtic goddess with the Thracian horseman – from Augustae (mod. Hurletz) near Koslodui on the Danube in NW Bulgaria. (1st – 2nd c. AD)

After G. Kazarow 1938, p. 84, Abb. 224. Now at National Archaeological Museum in Sofia, inv. No. 7518. (Thanks to Dr. E. Paunov)

Thus, the Epona cult continued to be popular in both northern and southern Thrace even after the Roman conquest, the influence of Celtic legions of the Roman army being instrumental in this phenomenon (see also Botoucharova 1949).

Statuette of Epona, 2/3rd century AD, from Alesia, Gaul

On Celtic legions in Thrace see:

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2012/05/24/hounds-of-the-empire-celtic-roman-legions-on-the-balkans/

Literature Cited

Benoît F. (1950) Les mythes de l’outre-tombe. Le cavalier à l’anguipède et l’écuyère Épona. Brussels, Latomus Revue d’études latines

Botoucharova L. (1949) Un nouveaux monument de la deese celto-romaine Epona. – In: RA, 1949, t. XXXIII

Green M. (1992) Animals in Celtic Life and Myth. London/New York

Kazarow (1938) Die Denkmaler des Thrakischen Reitergottes in Bulgarien I-II. Budapest, 1938 = Dissertationes Pannonicae ser. 2 fasc. 14.

Matasovic R. (2009) Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Leiden/Boston

Magnen R. and E. Thévenot (1953). Epona: déesse Gaulois des chevaux protectrice des cavaliers. Bordeaux

Tudor D. (1997) Corpus Momentorum Religionis Equitum Danuvinorum: The Analysis and Interpretation.