UD: Sept. 2019

“Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world.”

(Jacobsthal 1944)

(1st c. BC)

Human head (sandstone) discovered at the gate of the Celtic hillfort / oppidum at Závist in southern Prague. (Analysis has shown that the sculpture is complete, i.e. the head did not come from a statue). Such stone heads have been discovered in Celtic settlements and cult sites across Europe.

(2-1 c. BC)

Limestone sculpture from Mšecké Žehrovice in the Czech Republic

(1 c. BC)

In the year 1904 a rather strange artifact was discovered at an ancient burial site near the village of Deta (Timiş county), Romania. The ceramic head (0.30 – 0.35 cm in height) represents a bald male with neither facial hair nor eyebrows, a straight nose and a pointed chin (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 – The Deta Head

(after Rustoiu 2012)

Initially interpreted as part of a statue, and identified as ‘Prehistoric’ and ‘Bronze Age’, it has subsequently emerged that the Deta head, now dated to the late Iron Age (LTC1), comes from a Celtic kantharos of the ‘Danubian Type’, and represents one of many such Celtic anthropomorphic decorative elements / artifacts from this period recorded in south-eastern Europe.

The Danubian kantharoi represent a ceramic category adopted by the eastern Celts from a range of vessels specific to the Mediterranean region, and appear to have had special religious functions. 3 main types of Celtic kantharoi developed during this period (LTB2 – C1) – the 1st type consisting of close copies of Hellenistic originals, the 2nd type resembling local bowls to which 2 handles were added, and a 3rd type of large bi-truncated vessels, also with added handles (loc cit).

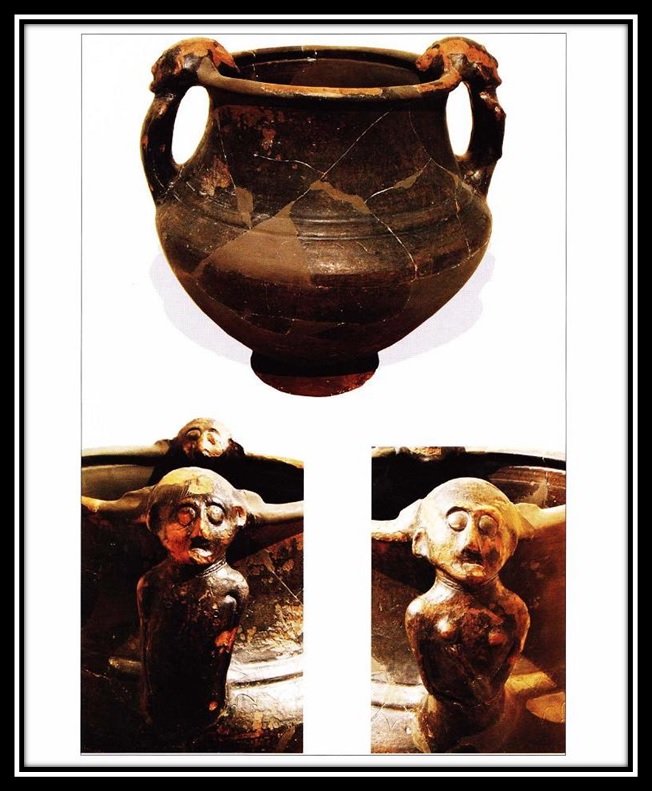

Fig. 2 – Celtic kantharos with anthropomorphic decoration from Blandiana, Alba County, Romania

(after Rustoiu, Egri 2010)

Kantharos with anthropomorphic handles from a Celtic warrior burial (#149) at Csepel Island, Budapest

(3rd c. BC)

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2015/01/24/celtic-budapest-the-burial-complex-from-csepel-island/

Variants of such vessels continued to be produced by the Balkan Celtic population right up to the Roman conquest at the end of the 1st c. BC, as has recently been confirmed by examples such as that used as a funeral urn in the female Celtic burial (#10) at the Bratya Daskalovi site (Stara Zagora region) in south-central Bulgaria which has been dated to the late 1st c. BC (Tonkova et al 2011). Such kantharoi, dating to the late 2nd/ 1st c. BC, have also been recorded at cult centres in Thrace, such as that at Babyak in the western Rhodope mountains of s.w. Bulgaria. At the latter site the kantharoi, along with other artefacts including metal objects and zoomorphic cult firepots, were ritually ‘killed’ in the typical Celtic fashion.

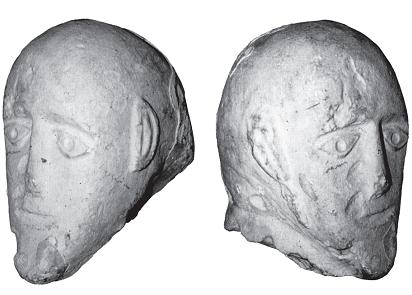

Other Celtic vessels with anthropomorphic decoration from s.e. Europe include examples such as the kantharos from burial #23 at Belgrad-Karaburma, and vessels from Kósd, Kakasd, Csepel Island, Balatonederics, Rogvágy, Levice, Blandiana, etc. The Deta head has particularly close stylistic parallels in 2 heads from vessels discovered at Kósd (Hungary) and a head from a limestone stele discovered at Ciulniţa (Romania), while the stone ‘Janus’ heads from the Roquepertuse site in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur région of southern France bear distinct similarities to these eastern Celtic examples (Rustoiu op cit.).

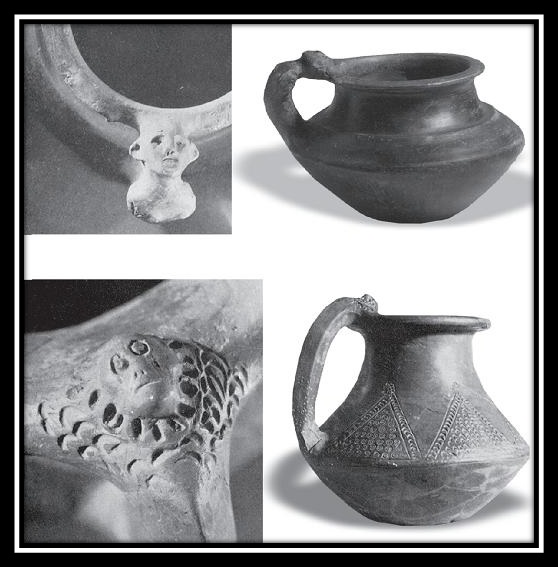

Upper end of handle on a pot from Balatonederics (Hungary) – 3rd c. BC

Fig. 3 – Anthropomorphic representations on the beakers from Kósd

(after Rustoiu 2012)

Fig. 4 – Head from a Limestone stele from Ciulniţa

(after Teleagă 2008)

Fig. 5 – ‘Janus’ Heads from Roquepertuse

The two-faced pre-Christian deity on Boa Island (Fermanagh), Ireland

Winged head on the obverse of a Celtic tetradrachm from western Hungary (late 2nd c. BC)

Bronze Celtiberian fibula from Lancia/Villasabariego (Castile and León), Spain. Note the decapitated head below the horses face.

(3/2 c. BC)

Further stylistic analogies to the aforementioned ceramic heads from Deta, Kósd, and the stone head from Ciulniţa have been identified (Rustoiu 2012) in a gold ‘Janus’ head pendant from the Schumen region of north-eastern Bulgaria, and a ceramic head dated to the same period (late 4th/ 3rd c. BC) from Seuthopolis in the so-called ‘Valley of the Thracian Kings’, as well as in the glass ‘face beads’ which became common in eastern Europe during the same period (loc cit; fig. 7 – 9).

Fig. 6 – Gold Celtic ‘Janus Head’ pendant from Schumen region, north-eastern Bulgaria

(3 c. BC)

Fig. 7 – Celtic ‘Face Beads’ from Romania

1: Mangalia 2: Pişcolt

Such glass ‘face beads’ have been unearthed in recent years during excavations at a number of sites in Bulgaria, such as Mogilanska Tumulus (Vratza region), Appolonia Pontica (Sozopol), Mavrova Tumulus (Starosel, Plovdiv region), Burgas, Kavarna (Dobruja region), etc.

Fig. 8 – Glass ‘Face Bead’ from Mogilanska Tumulus (Vratza region, Bulgaria)

Fig. 9 – Glass ‘face bead’ from Mavrova Tumulus (Starosel, Plovdiv region, Bulgaria)

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2013/02/04/the-celtic-evil-eye/

Previously ascribed to contact between the Hellenistic areas and the Celts of the Tyle state in eastern Bulgaria (Szabó 2000:11), it has subsequently emerged that in fact these appear earlier in the Celtic environment, as has been conclusively proven by examples discovered in burials # 191 and 202 (LT B1) or # 1, 16, 191, and 194 (LTB2) from Piscolţ in Romania (Rustoiu 2012).

La Tarasque de Noves. Anthropophagous statue from Noves in the Bouches-du-Rhône, France.

A dismembered limb hangs from its snarling mouth, and clutched in each front claw is a human skull. The statue is attributed to the Cavares tribe (/tribal federation), meaning “The Giants”.

(1st century BC)

Bronze applique in the form of a human head from a Celtic chariot burial at Roissy (Val-d’Oise), France

(3rd c. BC)

Literature Cited

Jacobsthal P. (1944) Early Celtic Art. Oxford

Rustoiu A., Egri M. (2010) Danubian Kantharoi – Almost Three Decades Later. In: Iron age Communities in the Carpathian Basin. Proceedings of the International Colloquium from Târgu Mureş, 9-11 October 2009.Cluj-Napoca 2010. P. 217-287

Rustoiu A. (2012) The Ceramic Human Head from Deta (Timiş County). About the La Têne Vessels with Anthropomorphic Decoration from the Carpathian Basin. In: Analele Banatului, S.N., Arheologie-Istorie, XX, 2012. Pp. 57-72

Teleagă E. (2008) Griechische Importe in den Nekropolen an der unteren Donau. 6 Jh. – Anfang des 3 Jh. v. Chr., Marburger Studien zur Vor- und Frügeschichte, Bd. 23, Rahden/Westf.

Тonkova, Gotcheva (2008) = Тонкова, М. и Гоцевa A.. Тракийското светилище при Бабяк и неговата археологическа среда. София

Tonkova et al (2011) = Трако-римски династичен център в районна Чирпанските възвишения Тонкова M. (ed.) София

Mac Congail

Thank you.

http://goddesschess.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/evidence-of-ancient-trade-glass-beads.html

very similar glass bead…i think might be celtic…congratulations for your work,…JUST GREAT..;-)

Have you heard of the heads from the Iron Age village of Ullastret, in Catalonia?

https://elpais.com/ccaa/2014/11/15/catalunya/1416082512_178457.html

Very interesting. Thank you.

First of all, thank you for all your hard work on this site, which has been very useful and informative.

I have noted in perusing your observations, that you seem to hold a similar opinion as regards the religious practices of the Celts, and their influences as the Celts first come into initial military confrontation with the Roman military / Eastern-style unit and command structure .

It seems to shock the Roman authors themselves that they were so soundly defeated in multiple early encounters, by a tribally organized barbarian population, that the system they were employing was ideally suited to overcome and defeat. My observation, is that these early Roman authors and commanders failed to comprehend a death cult, most likely similar in some facets to the Norse Valhalla. At least a berserker, elite grade of Celtic troops, who preceeded subsequent waves of attack were not attempting to survive combat, but were essentially seeking to die in the most outlandish, overt and deliberate manner possible, which the landed Roman troops, safe as long as they held their lines, failed to understand, to my view.

This brings me to the Gundestrup caldron, that you already cover to an extent within your site. The plate depicting the Horned one – Hern(e) [Isles Celtic] / Cern(unnos) [Continental and Alpine Celtic] is readily recognizable.

The plate depicting Taranis is also obvious. May rather demanding question for you concerns the ”dipping plate” on the Gundestrup caldron.

Can you identify within Celtic Mythology the action playing out on the dipping plate? While Hern/Cern(unnos) and Taranis are wearing their Torc, as are most other gods depicted on the plates, the large Dipper with horned mail wears no Torc. Is this a underworld helper, in your estimation?

My estimation is that this probably depicts the dead berzerker class entering the Celtic equivalent of Valhalla in which the incoming dead first-line troops (the last swordsman figure wears a wild boar crested celtic helmet similar to the (resurrected?) horseman. The dipping from this underworld helper revives the sacrificed (torc-less) battlefield dead, who respawn into elite horsemen who also no longer retain the Torc that was possibly the entry offering to the Horned one.

My question to you is, do you have a equivalent Isles/Continental Celtic legend to determine if this belief system was one of literal reincarnation, or is the process a Valhallic equivalent of a afterlife?

Thanks, i would really appreciate if you dedicated a page to analysis of the G.C. in detail, plate by plate, since its a fairly cohesive rosetta stone into otherwise murky or lost religious beliefs.

Interesting thoughts. All indications are that they believed in metempsychosis. https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2018/10/14/catubodua-metempsychosis-and-the-queen-of-death/ Whether the form of reincarnation was dependant on the previous life and manner of death is still unclear to me, as is the question of exactly who is the ‘Dipper’. At the moment the question of the exact geographical and temporal origin of the cauldron is becoming clearer. The key to this may be in the way the warriors are clothed. Do you have any thoughts on this.

I think your Scordisci attribution is very sensible. Bridal fittings on war horses being modeled after Thracian metalwork is fairly meaningless, since this type of stylistic borrowing in a mixed region means fairly little considering that the helmets, musical instruments, deities, style are all Celtic.

Whoever made it had to either have been in service as a mercenary in Africa, or was present in the Alps during the alliance with Hannibal, because the Elephant design is too realistic to have come from a 3rd party description. I doubt I could draw as accurate a Elephant picture that is as morphologically accurate, with many past trips to the zoo under my belt.

I think its a lot more likely that, with Celts the premiere metal workers of Europe,,.. the ghosted non-Celtic tracings are more credibly explainable as work once sketched out for a abandoned project commisioned by a neighboring Thracian settlement as opposed to the other way around.

The fact that it was disassembled but the plates were not ‘killed’ when it went into the ground in Denmark, would seem to indicate that it could possibly/likely have transported to Jutland by a group of surviving Cimbri, coming out of or through the contracting Alpine Celtic controlled lands, who may not have been fully Celtic or fully Germanic, as generally observed archeologically.

A lot of hypothetical I admit, but I also note that the hound greeting the line of underworld foot troops are met by a (admittedly mono-headed) hound which is holding the entrance ahead of the ‘dipping’ underworld helper.

Cerberus is the Hellenic hound guarding the entry to Hades, so it piques my interest that the hound in this case could be attributed to a earlier indo-euro legend that could have diverged at some point, but still links the guard dog serving the ‘dipper’ to the Hellenic beast famed to guard the underworld..

thanks again for all your excellent work and effort sir.

Thank you for your thoughts and interest. Have you seen the type of clothing worn by the warriors in other depictions? At the moment I’m looking at pinpointing the master who made the cauldron. Judging from other artifacts, looks likely to have been a Celto-Thracian master working in the Stara Zagora area of Bulgaria.