It has long been noted that the cult of the head “constitutes a persistent theme throughout all aspects of Celtic life spiritual and temporal, and the symbol of the severed head may be regarded as the most typical and universal of their religious attitudes” (Ross A. Pagan Celtic Britain. London 1967:163).

Strabo informs us that ‘when they depart from the battle they hang the heads of their enemies from the necks of their horses, and when they have brought them home, nail the spectacle to the entrance of their houses…’ (Strabo IV, 4,5). Amongst the Celts the human head ‘was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions, as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world’ (Jacobstahl P. Early Celtic Art. Oxford. 1944; see also Mac Congail 2010: 173-175). The severed head is also one of the main core symbols on Celtic artifacts and coins from the Balkans in the 4th – 1st c. BC.

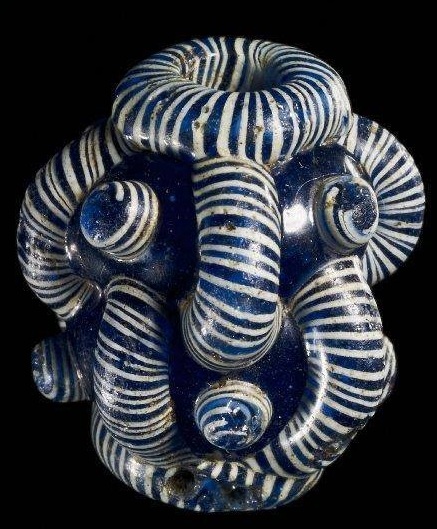

In this context, one of the most interesting types of glasswork produced by the Celts, apparently from Phoenician prototypes, were ‘Face/Head Beads’. These have been found at a number of Celtic burials and other sites from central (Germany, Switzerland etc.) and eastern Europe (Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria etc.).

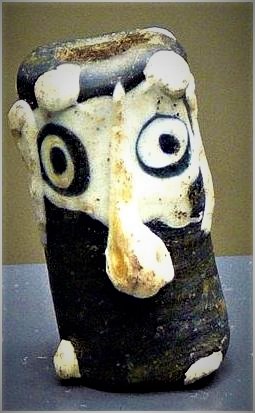

Celtic glass ‘Janus’ Face Bead from Mezönyarad (Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén), Hungary (3rd c. BC)

Celtic face bead from Moravia, Czech Republic (3 c. BC)

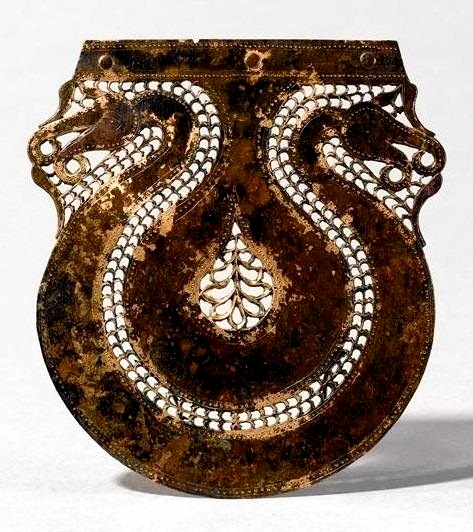

A wonderful example of this type of face bead from Bulgaria comes from the Mogilanska Tumulus (Vratza region), which has direct parallels in examples discovered at Celtic sites in the Czech Republic and Romania. Similar artifacts have been unearthed in recent years during excavations at other sites in Bulgaria such as Appolonia Pontica/Sozopol, Mavrova Tumulus (Starosel, Plovdiv region), Burgas, Kavarna, etc.

Face Bead from Mogilanska Tumulus (Vratza region, Bulgaria)

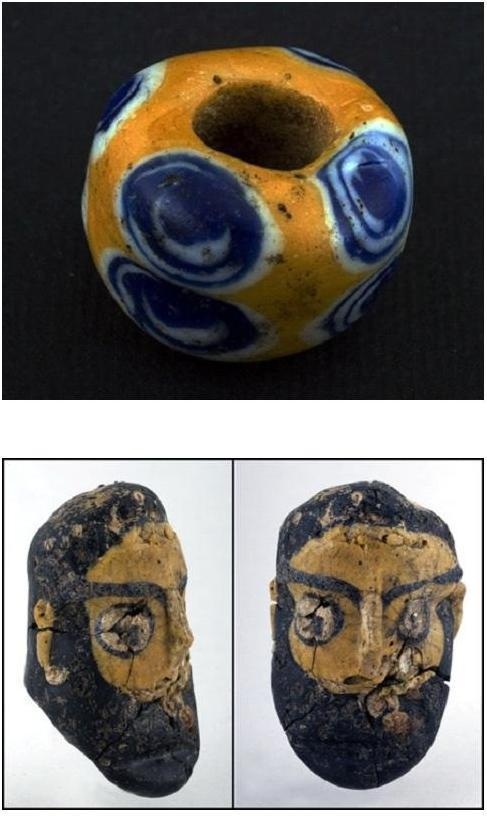

Glass bead and ‘face bead’ from Mavrova Tumulus (Starosel, Plovdiv region, Bulgaria)

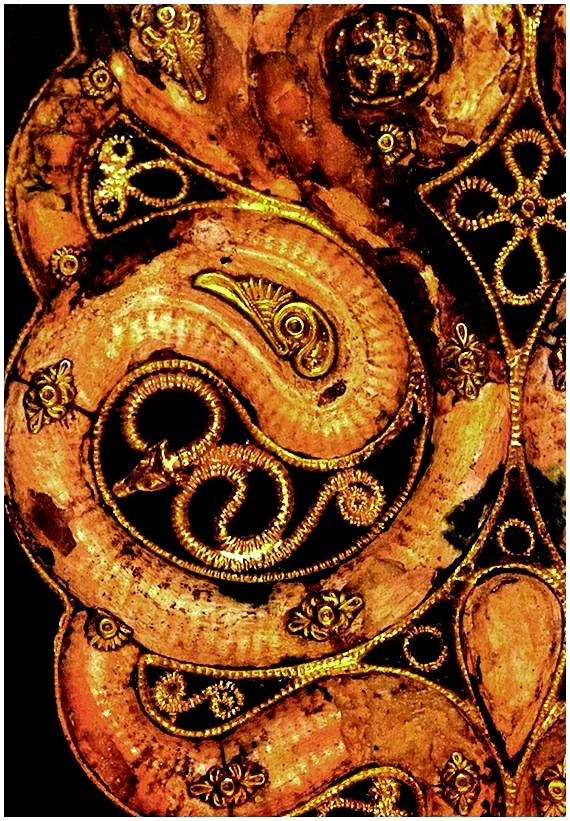

Also interesting, from an artistic perspective, is a gold ‘Janus head’ pendant executed in a repossé technique and decorated filigreé and granulation, discovered in the Shumen region of northeastern Bulgaria, and dated to the same period. From a morphological and stylistic perspective the closest analogies are the Celtic face beads found among the Celts of central and eastern Europe, examples of which come from sites such as Mangalia, Piscolt and Vác, as well as the aforementioned sites in Bulgaria (Rustoiu 2008).

Gold Celtic ‘Janus Head’ pendant from Schumen region, northeastern Bulgaria (4th/3rd c. BC)

As with many aspects of Celtic art, the tradition of producing face beads continues much later in the Insular sphere, as attested to by many wonderful examples of glass face beads dating to the late Iron Age discovered in Ireland.

Late Iron Age glass face bead from Antrim, Ireland

Mac Congail