The village of Koynare (Pleven region) is situated on the left bank of the Iskar river in north-western Bulgaria, an area which over the past century has yielded probably the highest concentration of Iron Age warrior burials in Europe – the vast majority discovered ‘accidentally’ by the local population (Domaradski 1984, Torbov 2000, Mac Gonagle 2013).

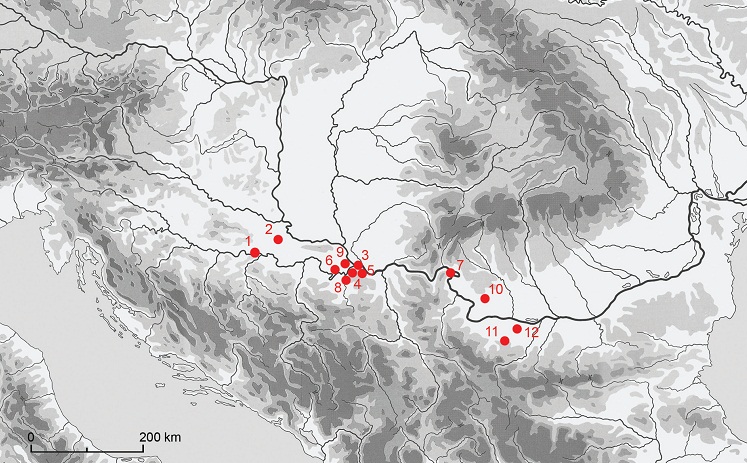

Finds of Celtic weapons and location of Koynare in north-western Bulgaria

(afte Paunov 2013)

The late Iron Age burial at Koynare has been dated to the La Tene D1 period (1st c. BC), and included material typical of a Balkan Celtic warrior burial of this period – La Tene sword/scabbard, circular shield umbo, spearheads, dagger (sica), and a H-shaped horse bit (Luczkiewiez, Schonfelder 2008).

SWORD/SCABBARD

Discovered together with fragments of its scabbard, the Koynare sword is one of over 60 examples of Celtic La Tene C2/D swords to have been discovered in the area of north-western Bulgaria between the Timok and Iskar rivers alone. These swords are identical to the Belgrade 2 / Mokronog 2-4, and Belgrade 3 / Mokronog 5-6 type Celtic swords from Scordisci burials in neighboring Serbia (Torbov 2000, Mac Gonagle 2013).

SHIELD UMBO

The circular shield umbo from Koynare is of the Novo Mesto type. Further examples of this specific type of Celtic shield have been recorded in north-western Bulgaria at Montana, Kriva Bara (Vratza reg.), Pleven etc. (Luczkiewiez, Schonfelder 2008).

Celtic (Scordisci) shield umbo from Montana, north-western Bulgaria (late 2nd c. BC)

SPEARHEADS

In terms of typology, the spearheads from Koynare have direct parallels in Balkan Celtic burials at Turnava and Biala Slatina (both Vratza reg.), and Montana in north-western Bulgaria, as well as an example from Portilor de Fier (Mehedinti) Romania – all similarly dated to the La Tene D1 period (loc cit). Spearheads are found in the vast majority of Balkan Celtic burials from this period. The presence of two examples, as at Koynare, is exceptional, but by no means unique. Such is the case, for example, with the recently discovered Scordisci warrior burial from Sremska Mitrovica (Serbia), which included two spearheads, one ritually ‘killed’.

(Ritually ‘killed’) spearhead from a Scordisci burial at Sremska Mitrovica (Serbia/1st c. BC)

(see Balkancelts ‘The Warrior and His Wife’ article, with relevant lit.)

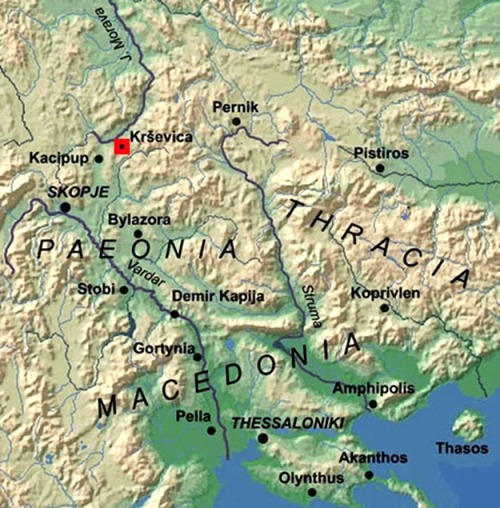

CURVED DAGGER

Curved daggers (sica) are a frequent part of the inventory of late Iron Age Scordisci warrior burials from the territory of modern Serbia, southern Romania and northern Bulgaria. For example, at the Scordisci necropolis at Karaburma (Belgrade) 7 such curved daggers, dating from the La Tene C2-D1 period, have been registered (burial nos. 13, 25, 32, 35, 66, 97, 112) (Todorovic 1972). Decorated daggers of this type, as the Koynare example, are most commonly found in Celtic burials from northern Bulgaria and Oltenia (southern Romania) (Luczkiewiez, Schonfelder 2008).

Celtic dagger (sica) from Montana, n.w. Bulgaria, decorated with mirored bird symbols

(See Balkancelts ‘Sacrificial Curved Daggers’ article)

HORSE BIT

The H-shaped horse bit discovered at Koynare suggests that, as in the case of Celtic burials such as those from Pavolche and Montana in north-western Bulgaria, or the recently discovered Scordisci burials from Desa in Romania, the individual in the Koynare burial was a Celtic cavalry officer.

H-Shaped horse bit and circular shield umbo from the Scordisci burials at Desa, Romania

(See Balkancelts ‘Desa’ article)

As at Koynare, the vast majority of Celtic burials from north-western Bulgaria date to the La Tene C2/D period – i.e. from the time of the Scordisci Wars with Rome in the late 2nd/1st c. BC, reflecting the high level of militarization in Celtic society in this area during the period in question.

However, the fact that only warrior burials have been discovered from this period, and those ‘accidentally’ by the local population, reflects a chronic lack of research at Celtic sites in the area, resulting in a continuing distortion in Bulgarian archaeological science.

Cited Literature

Luczkiewiez P., Schonfelder M. (2008) Untersuchungen Zur Ausstattung Eines Spateisenzeitlichen Reiterkriegers Aus Dem Sudlichen Karpaten Oder Balkanraum. Sonderdruch aus Jahrbuch des Romisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 55. Jahrgang 2008. p. 159-210

Mac Gonagle B. (2013) https://www.academia.edu/5385798/Scordisci_Swords_from_Northwestern_Bulgaria

Megaw J.V.S (2004) In The Footsteps of Brennos? Further Archaeological Evidence for Celts in the Balkans. In: Zwischen Karpaten und Agais. Rahden /Westf. p. 93-107

Paunov E. (2013) From Koine To Romanitas: The Numismatic Evidence for Roman Expansion and Settlement in Bulgaria in Antiquity (Moesia and Thrace, ca. 146 BC –AD 98/117) Phd.Thesis. School of History, Archaeology and Religion. Cardiff University. 2013)

Szabó M., Petres E. (1992) Decorated Weapons of the La Têne Iron Age in the Carpathian Basin. Inv. Praehist Hungariae 5 (Budapest 1992)

Todorović J. (1972) Praistorijska Karaburma, I, Beograd.

Tорбов Н. (2000) Мечове от III- I в. пр. Хр. открити в сиверосападна България. In: Исвестия на музеите в сиверосападна България. т. 28. 2000.