Mac Congail

The recently published numismatics collection from the Razgrad Regional Muesum (in today’s northeastern Bulgaria, see below) provides us with a valuable insight into the economic and geo-political situation in this region in the centuries directly proceeding the Roman conquest.

RAZGRAD

In the Razgrad area large amounts of La Têne material testifies to a Celtic presence from the 4th c. BC into the Roman period (see archaeology section). The main settlement in this area was at Abritus (Abritu), located in the Hisarlaka district of modern Razgrad, near the Beli Lom river. Despite the fact that it has hitherto been assumed that the settlement was initially of Roman origin, in light of the pre-Roman archaeological/numismatic evidence found in the area, and the geographical situation of Abritus on the Beli Lom river, it is appears that the name actually comes from the Celtic – abo- (Also recorded in Thrace as the first element of the Celtic settlements bearing the name ‘Ablana’ = river plain – see above) = river, and –ritu- = Ford (MIr -rith, OB rit, ret, OC rid (also in LNN), OW rit (LNN), MW ryt, W rhyd. ADA: 123-124; CPNE: 197-198; DGVB: 297; GPC: 3126; LEIA:R-34; PECA: 91; Falaliev DCCPN 2007; see ‘Celtic Settlements in Northern Bulgaria’ article).

Thus, the initial settlement at Abritu/Razgrad developed around a ford on the Beli Lom river, as the Celtic name suggests.

The Razgrad region of northeastern Bulgaria

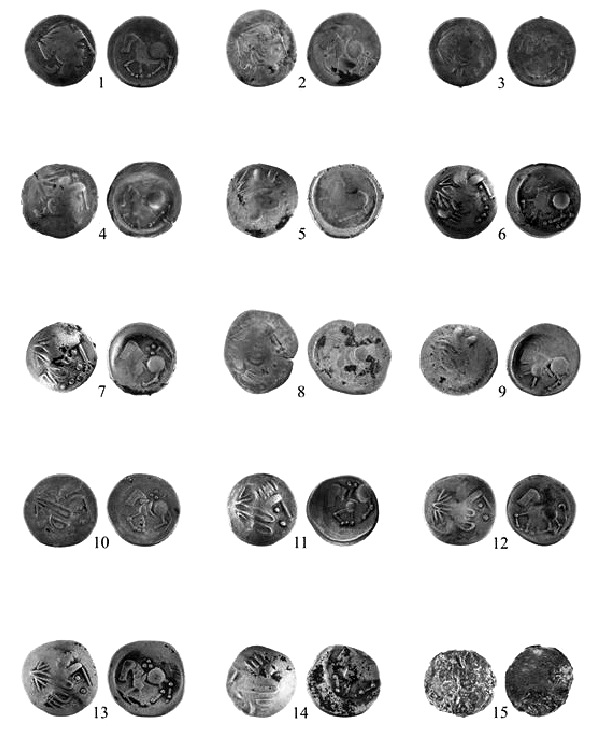

Locally produced (non-Hellenistic) coinage circulating in this region in the 3rd – 1st c. BC can be broadly broken into 4 main groups – Celtic imitations based on the Macedonian issues of Philip III and Philip II, Thraco-Celtic Thasos tetradrachms of the Thasos type, and bronze and lead Celtic issues based on the Odessos ‘Darsalas’ type coinage.

1. ‘Philip II’ Type

Celtic coins of the Philip II model are found on the territory of today’s Bulgaria almost exclusively north of the Balkan mountains (see Numismatics section 4, Map 4).

The high concentration of Philip II model Celtic coinage in northeastern Bulgaria is particularly interesting from a geo-political perspective. In this region the Banat and Saddle-Head (Sattlekopf)/Oltenia type(s) (Fig. 1-3) are most common. In northeastern Bulgaria this type of Celtic coinage has been found in particularly large concentrations in the Targovischte, Veliko Tarnovo, Razgrad and Russe areas where substantial numbers of Celtic Philip III, Thasos, and ‘Zaravetz type’ coins have also been registered (see below).

Fig. 1-2 – The Saddle-Head type (3rd – 2nd c. BC), the artistic predecessor of the extensive Oltenia type (2nd – 1st c. BC) (See numismatics section 4)

The Celtic “Philip II” type are distinguishable by the strong ‘barbarization’ of the images, the lack of an inscription, the diminishing of the size of the coin cores, and the lowering of the quality of the metal of the coins (Dzanev G. and Prokopov I. Numismatic Collection of the Historical Museum Razgrad (Anc. Abritus). In: Coin Collections and Coin Hoards from Bulgaria /CCCHBulg./ Volume I. Part 2. Sofia 2007; On the artistic evolution of Celtic coins in Thrace see ‘The Art of Rejection article’). A collective find of that type of imitation was discovered in Razgrad at the village of Hursovo, the municipality of Samuil (Razgrad region) Gerassimov, T. Monetni sakrovista, namereni v Bulgaria prez 1966 g., in: IAI, XXX, 1967, 190).

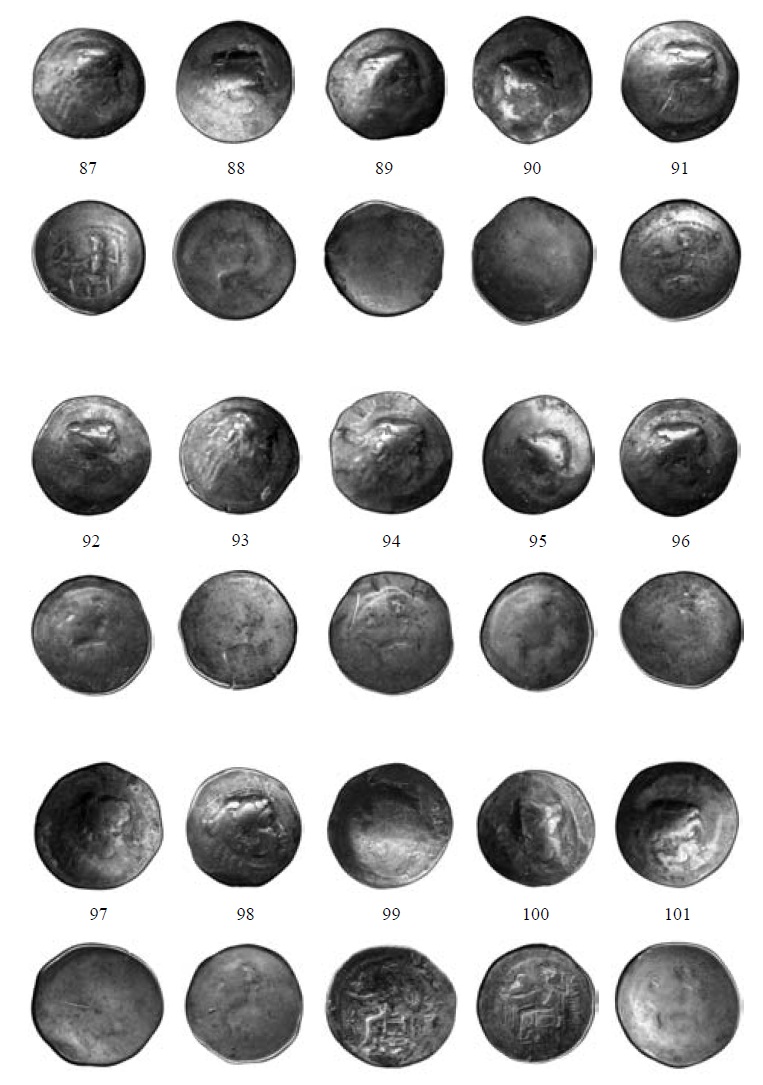

Fig. 3 – Celtic AR Philip II issues from the Razgrad Museum collection (2nd – 1st c. BC)

Göbl, OTA 300/1 – 305/5

(After Dzanev, Prokopov 2007)

Fig. 4 – Celtic tetradrachms of the Sattelkopfpferd/Oltenia type from Pirgovo/Mediolana, Russe Region (from the 1978 hoard), Northeastern Bulgaria

(see ‘The Mother Matrix’ article)

Other such finds of the Celtic Philip II type in eastern Bulgaria include those from the Veliko Tarnovo and Targovischte areas found at Gorsko Novo-Selo (Veliko Tarnovo region), Kruscheto (Veliko Tarnovo region), Lublen (Turgovischte region), Palamarza (Targovischte region), Veliko Tarnovo and Samovodene (Veliko Tarnovo region), as well as finds recorded at sites such as the Celtic hillfort at Arkovna (Dalgopol, Varna region), Sliven, Dobritsch, Schumen, and from Kavarna (Dobruja region) on the Black Sea coast (Numismatics section 4, Map 4).

Most impressive is the heavy concentration of Philip II model Celtic coins in the Rousse area on the Danube, to the northwest of Razgrad. The finds from Rousse itself, the Sredna Kupa district, and the nearby villages of Belyanovo, Mechka, Pirgovo, Slivo Pole, Nikolovo (On these finds see Numismatics section 4, with cited lit.), and Pissanets (Gerassimov, T. Kolektivni nachodki na moneti prez 1939 IBAI, XIII, 1939, 344; Shkorpil, K. An Inventory of the antiquities along the Roussenski Lom River, Sofia 1914, 47 (and item 46, 2) come from an area along the Danube where the Celtic settlements of Mediolana (modern-day Pirgovo), Tegris (modern-day Marten) and Transmarisca (modern-day Tutrakan) were situated (see ‘Celtic Settlements in Northern Bulgaria’ article). Numismatic data thus confirms the linguistic and archaeological evidence which indicates that the Russe/Razgrad area was one of the key political and economic centers of the Celtic culture in northeastern Bulgaria in the 3rd – 1st c. BC. Numerous finds of Celtic ‘Philip II’ type coinage have also been registered in other areas of modern day Bulgaria, particularly from the area of the Scordisci in the north west of the country (see Numismatics section 4).

In the case of a number of hoards the Celtic Philip II types have been found together with other Celtic coinage from the same period, for example the aforementioned hoards from Pirgovo, Belyanovo, and Mechka, as well as in the city of Russe – where the coins of the “Philip II” type were unearthed together with other Celtic types, notably the Philip III/Cavaros types outlined below.

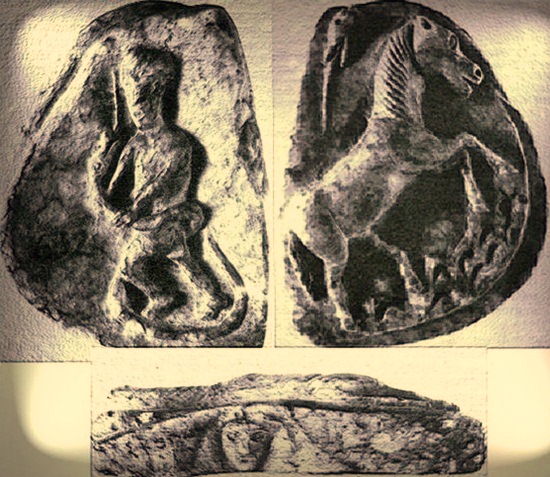

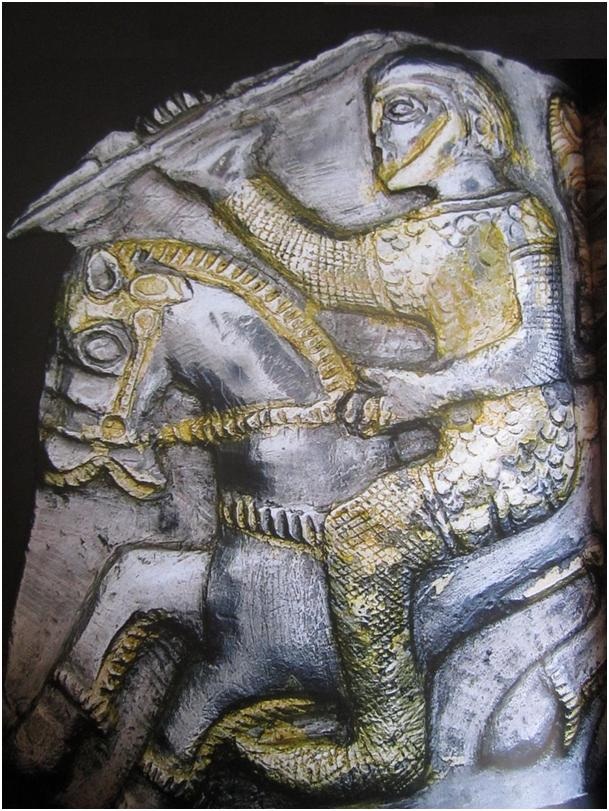

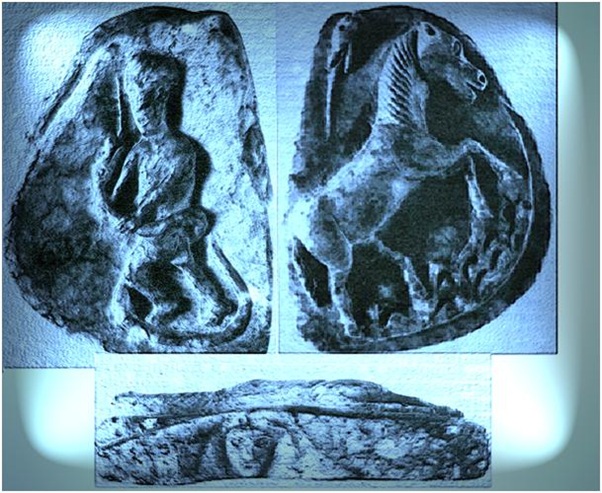

Fig 5 – Mother coin for the production of Celtic Sattlekopf/Oltenia issues, Rousse region

(See ‘The Mother Matric’ article)

2. PHILIP III/CAVAROS TYPE

Besides single finds, two major hoards of Celtic Philip III/Cavaros model coins have hitherto been found in the Razgrad area. The first was discovered in February 1940 when a find of 52 pieces of that type, placed in a pot, was uncovered just next to the southern end of the village of Kamenovo, the parish of Senovo. The hoard consists of early examples of this type of Celtic coinage, and from an artistic perspective should be dated to around the mid 2nd C. BC:

Fig. 5 – Celtic Philip III/Cavaros type issues from the Kamenovo Hoard (Razgrad region, northeastern Bulgaria)

(after Dzanev, Prokopov 2007)

In the 1950’s another large find of the same type of Celtic coins was uncovered on the land of the village of Kostandenets, (Tsar Kaloyan district, Razgrad region). Unfortunately, this hoard was stolen/dispersed, and is no longer available for scientific research (Dzanev, Prokopov op. cit.).

From a more general perspective, besides the aforementioned hoards from Pirgovo, Belyanovo and Mechka, as well as in the city of Russe – where the Celtic coins of the “Philip III” type were unearthed together with other Celtic issues, hoards consisting of imitations of only the “Philip III” type have been recorded across northern and central Bulgaria – for example, from the villages of Pepelina, and Ostritsa in the Rousse region, from the town of Gorna Oryahovitsa, from the village of Radanovo, in the region of Veliko Turnovo, from the area of Veliko Turnovo, from the village of Pordim, Pleven region, from the village of Alexandrovo, in the region of Lovetch, from the village of Smotchan, Lovetch region (see Lovech article), from the village of Glavatsi, in the region of Vratsa, from the village of Vrachesh, in the region of Botevgrad (Dzanev, Prokopov op cit.), etc. (On the circulation of these coins in Bulgaria see Numismatics section 1).

Particularly interesting are Celtic Philip III issues found in a hoard during recent excavations at Bratya Daskalovi, Stara Zagora region (South-Central Bulgaria) which, according to the authors (Prokopov, Paunov, Filipova 2011; see Numismatics section 1), indicates that this area of Thrace was also settled by a Celtic population in the immediate pre-Roman period.

Fig. 6 – Celtic (Philip III type) drachms, recently found together in a hoard at Bratya Daskalovi (Stara Zagora region, south-central Bulgaria). Together with Celtic ‘Thasos’ issues and a Roman Republican issue. The hoard has been dated to the late 1st c. BC.

(After Prokopov, Paunov, Filipova 2011; see Numismatics section 1)

3. ‘THASOS’

The third main ‘barbarian’ coinage in circulation in the Razgrad/Northeasten Bulgaria area in the immediate pre-Roman period was Thraco-Celtic imitations of the Thasos tetradrachma. Judging by the artistic features of these coins, which remain relatively close to the Hellenistic original, they should be dated to the last decades of the 2nd c. BC:

Fig. 7 – Early Thraco-Celtic Thasos ‘Imitations’ from the Razgrad Museum collection. Late 2nd c. BC.

(after Dzanev, Prokopov 2007;See Thasos article in Numismatics section; On the artistic evolution of Celtic Thasos imitations in Thrace in the 2nd/ 1st c. BC see Mac Congail, Krusseva (2010) – Mac Congail B., Krusseva B. The Men Who Became the Sun, Barbarian Art and Religion on the Balkans. Plovdiv)

Along with single finds of ‘Thasos’ imitations, a find consisting of an unknown number of tetradrachms of this type was uncovered to the west of the village of Krivnya, the parish of Senovo (Razgrad region) ‘some years ago’. Apparently, four tetradrachms plus one Roman Republican denarius from this hoard reached the local museum, and are enlisted in the register of the Museum collection of the village of Krivnya. However, after ‘a number of robberies’ the coins themselves have disappeared (Dzanev, Prokopov op cit.). Of another hoard of Thasos coins found at Lipnik (Razgrad district, Razgrad region), dated 90 / 80 BC (Prokopov, 2003:141 = Прокопов И., Няколко Бележки Върху Тасоските Тетрадрахми От Колекцията На Народния Музей В Белград. In: Известия на Катедра Българска история и археология и Катедра Обща история – ЮЗУ ‘Неофит Рилски’ – Благоевград, 1/2003. P. 139-153), there is strangely no mention in the recent catalogue of the Numismatics Collection of the Razgrad Museum.

From a more general perspective, in the 2nd/1st c. BC the Celtic Thasos ‘imitations’ were in circulation virtually over the entire territory of today’s Bulgaria (see Numismatics section 2). Most noteworthy is the concentration of these coins in the region of central Bulgaria called – especially in the area east of Plovdiv stretching to Nova Zagora. As mentioned, in the Chirpan/ Bratya Daskalovi district (Stara Zagora Region) recent excavations have uncovered such Celtic Thasos model tetradrachms together with other Celtic coins. This data, in combination with other previous such finds from this area of Bulgaria (from Benkovski, Kolyo Marinovo, Medovo, Naidenovo, Bolyarino, Nova Zagora, Stara Zagora, and Zetovo) strongly suggests that this was an important center for the production of Celtic coins of the ‘Thasos’ type in the 2nd / 1st c. BC (op cit).

Fig. 8 – Late Celtic tetradrachmas of the Thasos type, dated circa 50 BC

Bratya Daskalovi, Stara Zagora region (After Prokopov et al 2011; see Numismatics section 2 – Thasos)

Also interesting is the number of finds along the Maritza (Hebros) river valley in the Plovdiv and Haskovo regions of Bulgaria, which suggests continuing trade contacts between the Celtic and Thracian tribes of the interior with the Aegean during the 1st c. BC. While other Celtic coinage from this period is localized in certain areas of Bulgaria, the Thasos model is found in all areas of the country, frequently together with other Celtic, Hellenistic or Roman coins. This would appear to indicate that the Celtic Thasos ‘imitations’ represented a de facto ‘pan-barbarian’ currency among the native Thracian and Celtic population of today’s Bulgaria in the pre-Roman period.

4. ‘ZARAVETZ’ ISSUES

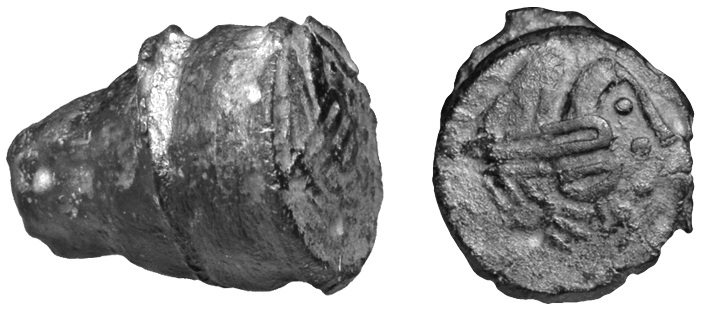

Most interesting of the Celtic coinage recorded in the Razgrad region are local Celtic issues. Particularly surprising is the presence of Celtic Strymon/Trident type bronze issues in the Razgrad area. Finds of this type of coinage, which was produced by the Celtic tribes in western Bulgaria in the 2nd/ 1st c. BC (see Numismatics Section 6), in the Razgrad region, indicates trade links between the Celtic tribes in the west and northeast of modern Bulgaria.

Fig. 9- Celtic Strymon/Trident Bronze issue from the Razgrad Museum collection.

(after Dzanev, Prokopov 2007)

Perhaps most interesting in the Razgrad Museum collection are bronze issues of the Celtic ‘Zaravetz’ type, dating to the 3rd/ 2nd c. BC. The Celtic Zaravetz type coins are based on autonomous bronze emissions of the Greek colony of Odessos which had been previously dated generally to the 3rd – 1st c. BC. The fact that the Celtic ‘imitations’ have been found in an archaeological context which dates to the end of the 3rd – beginning of the 2nd c. BC logically dates the Greek prototype to the period prior to the end of the 3rd c. BC (see numismatics section 8 – ‘Zaravetz’).

In terms of distribution the Zaravetz issues bronze and lead issues have been discovered in an area which includes most of present day northeastern Bulgaria, with a particularly high concentration in the Veliko Tarnovo area. Besides the Zaravetz hillfort , further examples have been recorded in Veliko Tarnovo itself, the Hill(fort) at Rachovetz – 7 km. north of Veliko Tarnovo, and in the vicinity of the village of Samovodene, slightly to the west of Veliko Tarnovo. Other finds have been recorded in northeastern Bulgaria at Byala (Russe region), Schumen, Tutrakan (Silestra region), Opaka (Targovischte region), from Razgrad, as well as in large numbers from the western Varna region (op cit).

Fig. 10 – Celtic ‘Zaravetz’ bronze issues from the Razgrad Museum collection

(after Dzanev, Prokopov 2007)

The recently published numismatic evidence from the Razgrad Museum collection confirms that the coinage produced by the local population in the Thracian interior of northeastern Bulgaria in the late Iron Age ranged from Celtic silver issues of the Philip II, Philip III and Thasos types, to lower value coinage which consisted of the aforementioned Zaravetz bronze and lead issues. This broad spectrum of coinage of differing intrinsic and economic value indicates a highly developed and organized economic system among the ‘barbarian’ population of this area of northeastern Bulgaria in the pre-Roman period.