UD: Jan. 2019

“And those who pacify with blood accursed

Savage Teutates, Hesus’ horrid shrines,

And Taranis’ altars cruel as were those

Loved by Diana, goddess of the north”.

Lucanus (Pharsalia, Book 1)

The three Celtic deities best known from classical sources are Teutates, Esus, and Taranis. Teutates is identified with Mars or Mercury, and receives as human sacrifice drowned captives and fallen warriors. Esus too is identified with Mercury, but also with Mars, and he accepts as sacrifice prisoners who are hanged on trees and then dismembered.

The Celtic ‘Thunder-God’ – Taranis, who is also known from nine inscriptions found in Italy, Germany, Hungary, Croatia, France and Belgium, and figures as the character of Taran in the Cymric (Welsh) Mabinogi of Branwen ferch Llŷr, is identified with Jupiter, as a warlord and a sky god. Human sacrifices to Taranis were made by burning prisoners (Mac Congail/Krusseva 2010).

Taranis (with wheel and thunderbolt) (0.103 m.)

(Le Chatelet, Gourzon, (Haute-Marne), France)

Noteworthy is the fact that the main Celtic God, Lugh/Lugus, is not mentioned by Lucanus (op cit), leading to the suggestion of Rübekeil (2003:38), in view of his hypothesis of a Celtic origin of the Germanic god Odin, that Lugus refers to the trinity Teutates-Esus-Taranis considered as a single god (Rübekeil L. Wodan und andere forschungsgeschichtliche Leichen: exhumiert, Beiträge zur Namenforschung 38 (2003), 25–42).

Based on writings in the ninth century comment on Lucan, the Berne Scholia, and descriptions in Caesar’s De Bello Gallica, Taranis has been identified as the deity to whom both Julius Caesar and Strabo describe human sacrifices being offered by being burnt alive in ‘wicker men’. The Berne Scholia also describes Taranis as a ‘master of war’, and links him with the Roman deity Jupiter. Taranis’ name is derived from the Proto-Celtic root *torano- ‘thunder’ [Noun] (GOlD: Olr. torann – ‘thunder, noise’ W: MW taran [f] ‘(peal of) thunder, thunderclap’, BRET: OBret. taran gl. tonitru, MoBret. taran [m] CO: OCo. taran gl. tonitruum, MCo. taran).

Jupiter Taranis – Roman era statue of Taranis syncretised with Jupiter, with eagle and solar/Taranis wheel (attributes of the respective deities) in the Musée lapidaire d’Avignon.

The Gaulish word for ‘thunder’ is preserved in the Gasconian dialect of French (taram). The Celtic forms are best explained by a metathesis *tonaro- > *torano-. The unmetathesized form is perhaps attested as the OBrit. Theonym Tanaro and in the old name of the river Po, Tanarus ‘thundering’. (REF: LEIA T-l13, GPC III: 3447, Delamarre 290, Deshayes 2003: 714; See Matasovic R., Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Leinen/Boston 2009. P. 384, with relevant lit.).

Fragment of bone with inscription to Taranis in a Celto-Etruscan script, from Tesero di Sottopendonda (Trente) Italy (4/3 c. BC)

THE WHEEL OF TARANIS

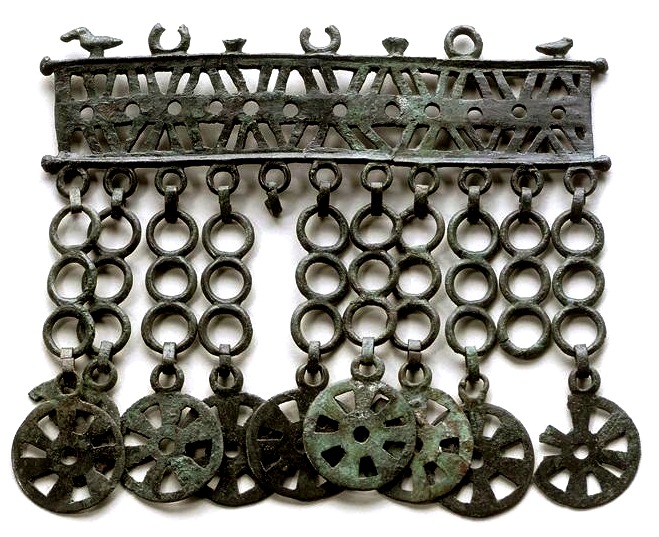

Bronze applique, decorated with zoomorphic/bird figures and solar/Taranis wheels, discovered in the Forest of Moidons (Burgandy), France

(6th c. BC)

Stallion with 3 penises, under Taranis wheel – reverse of a Celtic issue of the Tótfalu type from western Hungary (2c. BC)

Associated with the Celtic Thunder God is the Solar Wheel or Wheel of Taranis. The wheel was an important symbol in Celtic polytheism, associated with a specific god, known as the wheel-god, identified as the sky-, sun-, or thunder-god, whose name is attested to as Taranis by Lucanus (op cit). Numerous representations of the Wheel of Taranis are found on coins and other artifacts across Celtic Europe, from Britain in the west to Thrace in the east:

8-spoked votive wheels (rouelles / bronze), thought to correspond to the cult of Taranis. Thousands of such wheels have been found in sanctuaries and other sites across Celtic Europe.

(Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, France)

8-spoked (lead) votive Taranis wheel from the Celtic (Scordisci) settlement at Čurug, Vojvodina Province, Serbia (2-1 c. BC)

Gold beads and pendants, including solar/Taranis wheels, from the Celtic Szárazd-Regöly hoard, discovered in a swamp near Regöly hillfort (Tolna), Hungary

(1st c. BC)

Gaul. Aedui tribe. (Circa 80-50 BC)

AR Quinarius. Helmeted head of Roma left / horse prancing left, Wheel of Taranis below.

Reverse of a Balkan Celtic tetradrachm from central Bulgaria. Note the solar/Taranis wheel in the top left corner.

(1st c. BC)

https://www.academia.edu/6144182/Celtic_Thasos_Type_Coinage_from_Central_Bulgaria

Obverse of a quarter stater of the Caletes tribe with solar/Taranis wheel on the subjects face, discovered at Bordeaux-Saint-Clair (Haute-Normandie), France (1 c. BC)

Belgic Gaul, Treviri AV Stater. ca. 60–30/25 BC.

Belgic Gaul, Treviri AV Stater. ca. 60–30/25 BC.

Celticized horse rearing left, in upper field star, V with dotted border, & cross with four annulets between arms, pellet-cross under belly, star under tail; Wheel of Taranis, two stars & globule in front, above a row of pellets, herringbone pattern, solid line above which three stars.

THUNDER ON THE BALKANS

In southeastern Europe a range of Celtic artifacts have also been found which depict the Wheel of Taranis. The Celtic deity holding the solar wheel is represented, for example, on Plate C of the Gundestrup Cauldron thought to have been produced by the Thraco-Celtic Scordisci tribes in northwestern Bulgaria in the late 2nd c. BC. Artifacts depicting the Wheel of Taranis in this region range from Celtic coins dating from the 3rd c. BC onwards, to Romano-Celtic artifacts from the same region dating to the 3rd/4th c. AD.

Taranis with Wheel as depicted on plate C of the Gundestrup cauldron

In the 20’s of the 2nd c. BC the Scordisci tribe in Thrace came under attack from the north. An expansion of the Germanic Cimbri tribe was finally repulsed near the Celtic settlement of Singidunum (Belgrade), and the Cimbri migrated further west (Rankin D. Celts and the Classical World. New York 1987:19 ). It is likely that it was during these events that the most famous of Scordisci treasures, the Gundestrup cauldron, was looted and carried off by the Cimbri (Bergquist A.K., Taylor T.F. The Origin of the Gundestrup Cauldron, Antiquity, vol. 61, 1987. 10-24).

See also:

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2012/05/12/the-scordisci-wars/

Celtic tetradrachms from the Ribnjacka Hoard (Bjelovar, Croatia) – 2nd / 1st c. BC. Note the Wheel of Taranis in front of the horseman on the reverse. A large number of tetradrachms found in this hoard bore the symbol of the Taranis Wheel (Nos. 45 – 64).

(After Kos P., Mirnik I. The Ribnjacka Hoard (Bjelovar, Croatia). In The Numismatic Chronicle 159 (1999)

Celtic belt buckle of the Laminci type with Taranis Wheel from Dalj, eastern Croatia (1 c. BC)

https://balkancelts.wordpress.com/2014/08/14/a-taranis-belt-buckle-from-dalj-eastern-croatia/

Scordisci AR Drachm. Dachreiter type. Serbia/Bulgaria (2/ 1 c. BC)

Laureate head right / Horse trotting left. Wheel of Taranis above

Evidence for the worship of Taranis across Europe, and the depiction of the Solar Wheel associated with this Celtic deity on coins and other artifacts, is particularly important as it again illustrates that although regional differences existed between the pan-Celtic peoples in terms of material culture, certain core religious beliefs and iconography were shared, and remained constant despite temporal and geographic dispersion.

Mac Congail

This is amazing!

I have found a similar wheel in my garden to those above – has anyone got any idea how I can identify it for sure?

Depends on a number of things – size, material and your location. Did u find anything else in that area?

location was Hertfordshire UK – nothing else found in location but it could have come in in some top soil I had delivered the year previously. The item is some sort of metal approx 4.5 cm wide and the gap in the circumference looks deliberate – rather than broken. I thought at first it was a wheel of a childs toy? but there is no axle or anything that looks like it might attach to something else. A mystery?

Sounds like a votive wheel. But without an archaeological context it’s impossible to be sure.

God Esus is Asus… Absolutely known Scandinavian God’s range… God supporter to the human abilities. Oposite to the God’s range Van (suporter to the places potence). Cult of Taranis appeared in the East of Jutlandia as the Cymbrian oposite cult to the Western Balts serpent’s cult, which has the very hard and agressive priests organisation (with the very known snake’s heads axes and so on)

The Jupiter/’Taranis’ statue from Le Chatelet could also be interpreted as a man holding a chariot wheel, axle and harness buckles… now, where’s that horse? Linguistically, it is worth adding that ‘Taran’ was a name for an unbaptized spirit in Gaelic Scotland.

Interesting. It appears that many of the Celtic deities survived in corrupted forms in the insular realm, transformed during the christian period into ‘evil’ entities.

Assuming there were actually many Celtic deities, of course… most of the insular divinities were actually turned into saints rather than devils! 😉

Worth bearing in mind when reading Lucan’s ‘Pharsalia’: he almost quotes Caesar in his account, no doubt adding a few details to bolster his reputation for originality. The main difference (apart from Hesus, Taranis, Di Ana etc getting a name-check) is that Lucan employs circumlocution to digress on the flaming fallen pride of the barbarian warriors, where Caesar simply refers to ‘Mercury’ as the Gauls’ favourite deity and notes that they ‘have many images of him’. How people haven’t seen this as a reference to the ‘foliate head’ image of Alexander/Phillip/Apollo/Ammon on their many remarkable coins is beyond me! How are the mighty, proud and mercurial fallen… a telling indictment upon those troublesome hoards who thronged the land just north of horse-loving Macedonia. Lucan makes the groves of Taranis & co sound like Cassius Dio’s vengeance shrine of ‘Andate’ at Camulodunum/Londinium/wherever ca. AD61. ‘Andate’ is not a million miles short of ‘An Dagda’ is it? Now about those tricephalad statues that keep cropping up…

We should probably take Greek and Roman sources on Celtic religion with a huge pinch of salt. Personally I believe many answers may be found in their coins, which have been substantially neglected as a source of information on their beliefs and deities.

What really interests me is the influence of the religious culture of the northern/central European Bronze Age civilisations upon the development of traditions such as Orphism in ancient Greece, via Thrace. ‘Celtic’ material culture of the Iron Age was surely a version of this dominated by a superadded warrior/warband culture which became highly mobile and broadly influential from the 5thC/4thC BCE.

What are your opinions about this?

As you may have noticed, we have mostly restricted ourselves to the Iron Age expansion into the east of the 4th/3rd c. BC onwards. From my observations, the Thracian cultural/religious traditions (at least those of the Thraco-Macedonian elite/Odryssae) are strongly Hellenized by the late 5th/early 4th c. BC, and thus it is very difficult to work out what exactly is ‘Thracian’ in the pure sense. Also, it is my view that much of the linguistic evidence concerning ‘Thracian’ is dubious, as many Celtic elements have been included in the study of the ‘Thracian’ language. For example – https://www.academia.edu/3292310/The_Thracian_Myth_-_Celtic_Personal_Names_in_Thrace

This aside, it is my ‘gut feeling’ from provisional study of the topographic and anthroponymic evidence that there is simply too much coincidence between them (Thracian and Celtic) for there not to have been close contact between these groups prior to the later eastern Celtic expansion. It is something that I cannot yet prove conclusively, but I suspect that they had previously formed a single ethnic entity. The exact chronology of when this existed is complicated by the fact that most linguistic evidence comes from the late Hellenistic’and Roman periods, by which time mixed Thraco-Celtic cultural groups had evolved in Thrace. This later cultural fusion further complicates the linguistic evidence, but the question may possibly be clarified by working backwards…

I gather that there is still some cognitive dissonance between the cultural identifiers ‘celtic’ and ‘slavic’ – a bit like the breaks between ‘celtic’ and ‘germanic’. It’s a shame – but nice to see that people like you are working on describing the underlying metaculture!

I have been reading up on celtic coins recently because I am including them in a painting I am working on. One coin in particular, which I have had identified as coming from Trier, Germany about 50 BC, looks remarkably like the layout of Stonehenge. The “cursus” radiate from a single point to form a “V”. Within the V are two concentric rings with a center dot which is pierced by an

alley on the same radial course as the cursus. Little hillocks, or tumeri, are sprinkled about the perimeter. Has anyone else noticed this? It is very much like the Belgic Gaul coin above, but instead of the wheel has the two concentric rings with alley piercing them.

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft and commented:

Der Gott des Rades