(Updated May 2013)

‘In dama huair ann ba rigan roisclethan ro alainn;

Ocus in uair aill… na baidb biraigh banghalis’.

(At one moment she was a broad-eyed, most beautiful queen,

And another time a beaked, white-grey badb)

(Harleian manuscript 4.22)

The central tenant of Celtic religion was metempsychosis – the transmigration of the soul and its reincarnation after death. (Caesar J. De Bello Gallica, Book VI, XIV) This belief is probably best summed up by the Roman poet Lucanus (1st c. AD):

While you, ye Druids, when the war was done,

To mysteries strange and hateful rites returned:

To you alone ’tis given the heavenly gods

To know or not to know; secluded groves

Your dwelling-place, and forests far remote.

If what ye sing be true, the shades of men

Seek not the dismal homes of Erebus

Or death’s pale kingdoms; but the breath of life

Still rules these bodies in another age-

Life on this hand and that, and death between.

Happy the peoples ‘neath the Northern Star

In this their false belief; for them no fear

Of that which frights all others: they with hands

And hearts undaunted rush upon the foe

And scorn to spare the life that shall return.

Pharsalia Book 1, (453-456)

In the transportation of the soul from one world to the next birds of prey played a central role:

‘to these men death in battle is glorious;

And they consider it a crime to bury the body of such a warrior;

For they believe that the soul goes up to the gods in heaven,

If the body is exposed on the field to be devoured by the birds of prey’.

(Silius Italicus (2nd c. AD) Punica 3 340-343)

‘those who laid down their lives in war they regard as noble, heroic and full of valor,

And them cast to the vultures believing this bird to be sacred’

(Claudius Aelianus. De Natur. Anim. X. 22)

The removal of flesh from corpses, which is well documented in the Celtic world, had a mortuary significance that differed greatly from the Greco-Roman practices (Soprena Genzor 1995: 198 ff.). The last 25 years of research have revealed how interments were the culmination of previous very complex rituals. The removal of flesh before interment is clearly attested at Celtic sanctuaries like Ribemont (Brunaux 2004: 103-24), but the enormous deficit of interments, especially in the late La Têne period, can be partially explained by the exposure of corpses with the consequent destruction of most of the skeleton. This exposure ritual was a genuine self-sacrifice, as the enemy who had taken the life of the warrior, just as the bird of prey who devoured him, was merely the hand of the god. (Soprena 1995; Brunaux 2004: 118-24)

This process is illustrated, for example, on the Celtiberian golden diadem from Asturias which shows the bird metamorphosis of the human figures during their final journey.

Fig. 2 – Detail from the Asturias diadem (After Marco Simón 2008)

On the Balkans the same ritual is described by Pausanias (X, 21, 3) in connection with the Celtic migration into the Balkans at the beginning of the 3rd c. BC. Celtic warriors who fell in battle during the invasion of Greece were likewise left exposed to be devoured by birds of prey, consistent with the religious practice outlined above (Churchin 1995; Mac Congail 2010: 57).

In light of the significance given to birds of prey in Celtic culture it is interesting to note the ‘name’ of the leader of the Celtic offensive on Greece at the beginning of the 3rd c. BC, the same as that of the chieftain who led the Celtic tribes who sacked Rome a century earlier – Brennos. It is unlikely that this is coincidence, and it appears that Brennos was not a personal name, but a military title given to the overall commander of a Celtic army drawn from different tribes. The term comes from the Proto-Celtic *brano- (Matasović R. 2009. Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic; see also Mac Congail 2010: 54-59) and means literally The Raven.

The importance of the raven, and birds of prey in general, in Celtic culture and religion is archaeologically confirmed by their frequent appearance on Celtic artifacts and coins. For example, of the more than 500 Celtic brooches with representational decoration now known, from Bulgaria in the east to Spain in the west, more than half depict birds (Megaw 2001: 87). On the Balkans birds of prey also appear on artifacts such as the Celtic helmet from Ciumesti (Romania) (see ‘Prince of Transylvania), similar examples of which are depicted on the Gundestrup cauldron (fig. 3) produced by the Scordisci in northwestern Bulgaria. Depictions of birds of prey are also found on the Celtic chariot fittings from Mezek in southern Bulgaria, and the Celtic sacrificial daggers from Romania and Bulgaria (see ‘Sacrificial Daggers’ article).

Fig. 3 – Detail from the Gundestrup Cauldron

THE DEATHRIDER

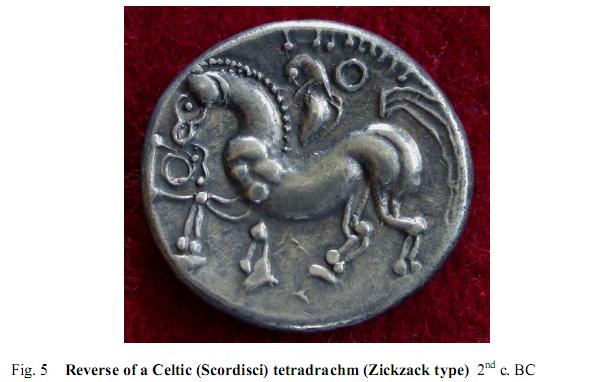

From Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary originate Celtic coins of both the Philip II (fig. 4/5) and Paeonia model (fig. 6/7) on which the ‘raven’ is depicted behind the left shoulder of the horseman, accompanying him into battle. The presence of the triskele on the Paeonia model coins in particular confirms the religious nature of the images. On the vogelreiter type (fig. 7), from the 3rd – 2nd c. BC, the horseman himself is portrayed as a skeleton, the ‘deathrider’ again accompanied by a raven.

THE RAVEN GODDESS

The Celts believed that the war-goddess, or more accurately the mother goddess in her war mien, appeared to warriors slain in battle in the form of a bird of prey, most often a crow or raven (O h’Ogain 2002: 22; Mackillop 2004:30; Mac Congail 2010: 72-76). She was known as Catubodua (battle-raveness) which survived in later Celtic tradition as the Cathbhadhbh or Badhbh Chatha (loc cit).

This theme also appears on Celtic coins from the Balkans, in depictions of the mother goddess in her personification as the Badhbh Chatha / Battle Raven. Such is the case, for example, with her portrayal on Celtic Thasos model coins from Bulgaria (fig. 8) as well as some of the Celtic Paeonian ‘imitations’ (fig. 9).

Fig. 8 – Depiction of the Goddess on the Reverse of a Celtic Thasos model issue from Bulgaria

In fig. 9 the obverse portrays the central theme of transformation of the goddess, while the reverse is packed with religious symbolism including the triskele symbol and the Celtic inscription. The central image again portrays the mother-goddess in her personification as the war raven – Badhbh Chatha.

(Gobl 436; BMC 131)

Sources Cited

Brunaux J.L. (2004) Guerre et religion en Gaule. Essai d’anthropologie celtique. Paris: Errance.

Churchin L.A. (1995) The Unburied Dead at Thermopylae (279 BC) In: The Ancient History Bulletin 9: 68-71

Soprena Genzor G. (1995) Ética y ritual. Aproximación al estudio de la religiosidad de los pueblos celtibéricos. Zaragosa.

Mac Congail B., Krusseva B. (2010) The Men Who Became the Sun – Barbarian Art and Religion on the Balkans. Plovdiv. (In Bulgarian)

Mackillop, James (2004) A dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford University Press

Marco Simón F. (2008) Images of Transition. The Ways of Death in Celtic Hispania. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 74, 2008. Pp. 53-68.

Matasović R. (2009) Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Leiden and Boston

Megaw V., Megaw R. (2001) Celtic Art from its Beginnings to the Book of Kells. London.

Ó hÓgáin D. (2002) The Celts – A Chronological History. Cork.

Mac Congail

Download Pdf. Version of this Article: